Maryland Food Co-ops Born from Cooperative Movements: A Brief History

"It seems doubtful to me whether in the United States distributive cooperation will ever succeed. The prevalence of the evil credit system, the mixed nationalities of our citizens, and the excited, everlasting rush in industrial life, tend to render our people impatient and indifferent to the results obtainable in such a scheme...Only a slow-thinking, penny-counting, frugal and painstaking people can bring cooperation of any character to a success" (Adams, 1888, p. 502).

Most Marylanders would be surprised to learn that there was a time in the US when cooperative enterprises were well known and widespread, and that their state played a major role in its development. As early as 1794, Baltimore shoemakers formed the “first cooperative factory in the United States,” and later, from 1865 to 1888, industrial Baltimore was considered a “center for worker cooperatives” (Curl, 2011, p. 1-2). In the nineteenth century, important anti-corporate social movements paved the way for the formation of mutual aid societies by Black communities, union worker cooperatives, producer, and consumer cooperatives that became the core of Maryland’s cooperative legacy. Despite the waxing and waning in popularity of groups like the Odd Fellows, the Knights of Labor, and the Grange, these organizations had lasting impact on the formation of cooperative enterprises in the years before and after the turn of the twentieth century: “Well developed movements, we suggest, helped produce social ties and sustain cooperative forms as the United States shifted from a society of stable communities, local networks, and self-governing towns to a more diverse and impersonal society of geographically mobile strangers” (Schneiberg et al., 2008, p. 636).

In Maryland, mutual aid societies proliferated in the mid- and late-1800’s, setting the foundation for consumer cooperatives to develop. The association of Odd Fellows – a secret society originating in England that welcomed US chapters organized by Black men and women – grew to become the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows (GUOOF) (Wilson, 2022). These self-help groups, along with many other mutual aid organizations run by church groups or women’s groups, collected funds through membership to “cover the costs of burial, sickness, disability, and widowhood” (Ibid.). Referring to the Black-led organization, Adams writes in 1888, “The Odd Fellows were organized in Maryland as early as 1837 and claim an earlier and more direct descent from the English society than do their white brethren, having been formed under a charter brought out that year from the mother country. The order of the Good Samaritans was, perhaps, the next instituted, in 1841, and these two organizations now number their membership by thousands in Maryland alone” (Adams, 1888, p. 513). W. E. B. Du Bois counted thirty Black mutual aid societies in Baltimore as early as 1830. He credits these groups with not only providing aid but also building skills in cooperative economics and business that led to more formal cooperative enterprises (Nembhard, 2014, p. 74).

In the 1880’s in Baltimore and Washington (which at that time was part of Maryland), the Knights of Labor movement actively developed worker cooperatives among the large influx of European immigrants. These workers then became the patrons of grocery co-ops. From 1870-1890, the Knights of Labor are said to have sponsored over 200 worker cooperatives along with 50 to 60 consumer cooperatives throughout the US (Hoffman, 2022, pp.378-379). One grocery example in Baltimore was the Clinton Cooperative Company, which was “well patronized by the Knights of Labor” (Adams, 1888, p. 508). Curl states: “More than simply stores and community centers, [co-op grocery stores] were also venues for union organizing. But with a sharp fall of prices in the post-war period, many of them failed” (Curl, 2011, p. 2).

The National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry, now better known as The Grange, is an agricultural social and economic association credited with developing for farmers “the first successful widespread movement of Rochdale-type cooperatives in America” (Curl, 2012, p. 78). By the late 1880’s the Grange’s activities in Maryland were considered “the most successful” in the US southern region, with over 110 local chapters established in 1887 (Adams, 1888, p. 506). Many local chapters formed consumer cooperatives based on Rochdale principles to provide members and other shoppers goods at lower prices. While the Grange’s cooperative enterprises suffered financial troubles at the end of the century due to an economic downturn and fierce capitalistic pressure, the movement continued to be a social, educational, and advocacy source for farm communities in Maryland that led to many supportive agricultural cooperative laws, policies, and programs for farmers, including the Cooperative Extension Service and the Farm Credit System (Maryland State Grange, n.d.; Schneiberg et al., 2008). More broadly, Schneiberg ‘s research concludes that “Reformers and anticorporate movements successfully promoted and sustained cooperative enterprises across industries with very different economic characteristics, rendering them less dependent on peculiar economic forces, common cultures, and other idiosyncratic local conditions. In so doing, movements like the Grange helped institutionalize cooperatives and mutuals alongside corporations, fostering substantial and lasting organizational diversity within American corporate capitalism” ((Schneiberg et al., 2008, p. 657).

The early 20th century saw the rise of industrialism, consumerism and consumer rights. With the founding of the Cooperative League of the USA (CLUSA) in 1916, it was envisioned that the conscientious consumer would work in tandem with the labor movement, according to CLUSA’s Founding President, James Warbasse: “By itself, CLUSA saw the labor movement as constrained without the capacity to control consumption” (Steinman, 2019, p. 112). By the 1930’s, hundreds of consumer cooperatives were formed by labor unions, with Warbasse’s lofty goal for consumer cooperatives to “awaken the working class to the complete exploitative nature of capitalism and train the class to lead the cooperative economy” (Ibid.). Once the Great Depression began, consumer cooperatives doubled between 1933 and 1936 (Ibid., p. 115).

The Depression era and the establishment of the New Deal was the impetus for the Greenbelt Cooperative in 1937. Greenbelt, Maryland, newly incorporated in 1937, was planned as a low-income community for Washington DC workers with annual incomes of $1,800 or below (Cooper & Mohn, 1992). From its early days, co-op members played a role in comparative pricing and consumer education, and in fact, extended cooperative governance and education to the newly formed town. It must have helped that one of the leading co-op members worked at CLUSA as the editor of “Consumer Cooperation,” and could effectively communicate how Greenbelt was following in a long history of European cooperativism. Soon the town “boasted a cooperative nursery school and kindergarten, credit union, and health care association” (Ibid., p. 83). By 1968, Greenbelt Consumer Services, Inc. became the largest consumer cooperative in the country, with 23 supermarkets, 10 automotive service stations, 9 pharmacies and drugstores, furniture stores, bus line, and a movie theater, among other enterprises (Ibid., p. 239). Eventually this cooperative conglomerate became overextended. It was bought out in the 1980’s by another cooperative group that continues today as a successful grocery and pharmacy, known as the Greenbelt CO-OP Supermarket & Pharmacy (Greenbelt COOP supermarket and pharmacy).

Other Depression-era cooperatives in Maryland that can boast of long runs of operation include:

· The Montgomery Farm Women’s Cooperative Market, Bethesda, Maryland. A farmers market of women vendor members started through a University of Maryland cooperative extension program in 1932 and still in operation (Crook, 1982).

· Westminster Consumer Co-op, a traditional consumer grocery co-op in rural Westminster Maryland, incorporated in 1937, open for business in 1948, and closed in 2003 (Dayhoff, 2017).

The late sixties and seventies brought about civil rights, women’s rights, and anti-war “counterculture movements” that spurred on a new wave of food co-ops and buying clubs around the country and in Maryland. Responding to members’ calls for organic and local food as well as a need for centers forming political and economic alternatives to the injustices of the era, “an estimated five to ten thousand food co-ops (or “food conspiracies”) were started in the 1970’s” (Steinman, 2019, p. 120). In Maryland, these included startups like:

· GLUT Co-op, a Mount Rainier worker co-op started by conscientious objectors to the Vietnam War in 1969 and still in operation (GLUT Food Co-op, 2015).

· Maryland Food Collective, known as “The Co-op,” a student-founded worker co-op within the Student Union of the University of Maryland founded in 1975 and closed in 2019 (“Maryland Food Collective,” 2024).

· Bethesda Co-op, a union-backed consumer co-op established in 1975 in Bethesda and still in operation but moved to Cabin John, Maryland (Bethesda Co-op, n.d.).

· Takoma Park Silver Spring Co-op (dba TPSS Co-op) began in 1981 as a “vegetarian storefront” and continues today as a union consumer natural foods market (About & History, 2018).

In “Grocery Story: the Promise of Food Co-ops in the Age of Grocery Giants,” Jon Steinman describes the transition that many surviving co-ops had to take to navigate from the alternative, self-organized, anti-capitalist co-ops of the 70’s to the more conservative, yuppie culture of the 1980’s. Food co-ops had to “grow up” by introducing professional management and more rigorous business practices: “It was time to learn that ‘capital was different from ‘capitalism’ and being profitable meant staying in business. If they continued to rely on a non-traditional, erratic approach, co-op members could ‘burn out this hopeful alternative and doom the national movement to obsolescence’” (Ibid., p. 126).

Especially during their startup phase and early years, co-ops often relied on member labor to help with store operations. This reduced costs, kept prices low, and created a more engaged and social member community active in governance decisions (Ibid., p. 127). From the 1980’s to the 2020’s, due to a more restrictive labor laws and the trend toward professional management, volunteerism declined. In the 1990’s and 2000’s, established food co-ops often prospered from the new consumer demand for organic and local food, but not many new food co-ops startups succeeded (Steinman, 2019). Maryland examples still active today include:

· The Common Market in Frederick, Maryland was formed in 1974 as a buying club relying on member volunteerism for operations for nearly twenty years. It opened as a full-service grocery that served everyone, not just members, in 1990, and in 2020 opened a second, much larger storefront that continues to grow with over 10,000 members (Common Market, 2024).

· Catonsville Co-op Market started in 2011 as a buying club, incorporated in 2014 as a co-op, and has run a small all-volunteer weekly market in a church basement since 2015. Still without paid employees, it acts as a market, a buying club, and hosts events for its 475 members (Catonsville Co-op Market, n.d.).

· Valley Co-op in Hagerstown Maryland, started in 2010 as a buying club, and by 2014 was a 300-member, volunteer-run natural food storefront with limited hours. It moved to join the City’s Farmers Market in 2017. It was the only community-owned food co-op in Washington County until its closure in 2018 (Latimer, 2017) (Maryland.gov, n.d.).

The newest wave of interest in food co-ops has come from food sovereignty movements from both urban and rural communities who must travel a relatively long distance to access fresh and healthy food markets. Food co-op startups in Maryland for these communities seeking to gain control over their food choices have met with mixed success. Some examples include:

· The startup Cherry Hill Food Co-op was formed in 2022 to establish a community-owned grocery store in a low-income, low access community of South Baltimore. The nonprofit Black Yield Institute helped to plan with Cherry Hill partners to combat the community’s systemic barriers to healthy food and to develop food sovereignty. They currently hold a weekly market day in the Cherry Hill community as plans for a brick-and-mortar storefront are still developing (Black Yield Institute, n.d.) (Cherry Hill Food Co-op, n.d.).

· Cooperative Community Development, based in the Irvington neighborhood of Baltimore, is a community development nonprofit and co-op founded in 2022 planning to open a community-owned grocery store in a renovated building where workforce development, small business vendors, an innovation hub, and community center will fill the building (Cooperative Community Development, n.d.).

· Baltimore Food Co-op, based in the Remington area of Baltimore, opened its doors in 2011 with a great deal of media attention as a solution to low food access, but was quickly closed in 2012 (Tuesday et al., n.d.) (Maryland.gov, n.d.).

· Wholesome Harvest Co-op located in Frostburg, Maryland, is the only community-owned co-op in Allegany County (Wholesome Harvest Food Co-op, n.d.). Established in 2018, it serves as a specialty store, a deli, and partners with Food as Medicine affiliated doctors to deliver fresh groceries to seniors in the community (Ibid.).

· In 2023, the rural town of Poolesville in Montgomery County financed a feasibility study for a food co-op after residents noted on planning surveys that the town needed a local grocery store. While the study concurred that the town could sustain a local food co-op, recent elections may indicate that this is now less of a priority (Davis, 2024).

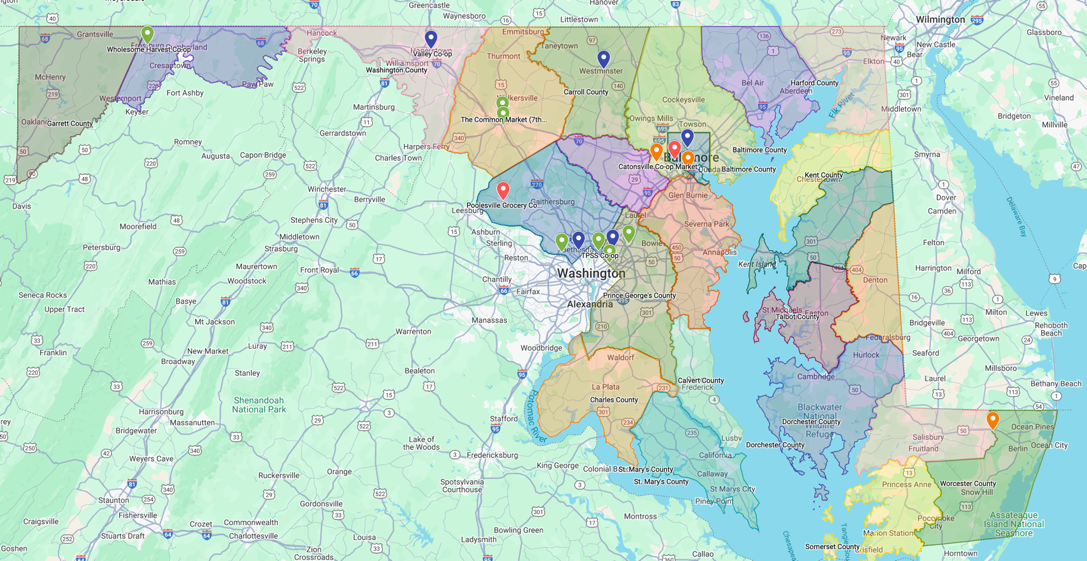

Below is a map of Maryland and its counties that pins the location of the food co-ops in planning and startup phases of development, those that are fully operational, and some of those that have stopped operating but had historical significance either for its longevity or for the co-op’s characteristics. While this list of food co-ops is almost certainly incomplete, it shows the breadth and variety of Maryland’s food co-op scene, as well as the range of eras when food co-ops got their start, those that operated briefly or for several decades before closing, those still going strong, and those yet to begin.

Born from waves of social movements that resisted corporate and capitalist pressures, Maryland food co-ops are part of a legacy of communities that chose to organize cooperatively. Whether Marylanders are aware of its roots or not, they benefit from this generational muscle memory of community solidarity. To build on this legacy, linkages among food co-ops of the past, present, and future deserve broader recognition and greater connection.

References

About & History. (2018, July 5). Takoma Park Silver Spring Co-Op. https://tpss.coop/about/

Adams, H. B. (1888). History of Cooperation in the United States. Johns Hopkins University. https://books.google.com/books?id=2WFea5kXmLYC

Bethesda Co-op. (n.d.). Once Upon a Time in 1975... Bethesda-Food-Co-Op. Retrieved June 6, 2025, from https://www.bethesdacoop.org

Black Yield Institute. (n.d.). Events. https://blackyieldinstitute.org/events/

Catonsville Co-op Market. (n.d.). What We Do. In Catonsville CO-OP Market (Vol. 2022, Issue Aug 11,). https://www.catonsvillecoop.com/what-we-do

Cherry Hill Food Co-op. (n.d.). Cherry Hill Food Co-op. https://snail-lizard-flzt.squarespace.com/

Common Market. (2024, December 12). Your Co-op | Common Market. https://www.commonmarket.coop/about/your-coop/

Cooper, D. H., & Mohn, P. H. (1992). The Greenbelt Cooperative: Success and Decline. IDEAS Working Paper Series from RePEc, Generic.

Cooperative Community Development. (n.d.). Projects. https://www.ccdgroup.org/projects-3

Crook, M. C. (1982, August). The Farm Women’s Market. The Montgomery County Story. https://montgomeryhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Farm-Womens-Market.final_.pdf

Curl, J. (2011). History of Cooperatives in the Baltimore-Washington DC Region. Worker Co-Operation and Collaboration in Baltimore & DC: Yesterday and Today, 1–6. https://geo.coop/sites/default/files/baltimorebooklet-7.pdf

Curl, J. (2012). For All the People: Uncovering the Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America. PM Press.

Davis, R. (2024, November). Rande(m) thoughts: Two big surprises coming from the Candidates’ Forum and who should win. Monocacy Monocle, 4. https://www.monocacymonocle.com/images/issues_2024/MM_2024-11.pdf

Dayhoff, K. (2017, September 29). Dayhoff: Co-op grocery story provided products, great service for more than 50 years. Baltimore Sun. https://www.baltimoresun.com/2017/09/29/dayhoff-co-op-grocery-story-provided-products-great-service-for-more-than-50-years/

GLUT Food Co-op. (2015, February 13). Mission & History. Glut Food Co-Op -- 301-779-1978. https://glut.org/mission/

Harris, S. (2024, May 28). Greenbelt’s Co-op Supermarket celebrates! Here’s highlights from its history. Greenbelt Online. https://www.greenbeltonline.org/greenbelt-co-op-supermarket-anniversary-celebration-and-history/

Latimer, J. (2017). Valley Co-op moves to City’s Farmer’s Market. DC News Now. https://www.dcnewsnow.com/news/valley-co-op-moves-to-citys-farmers-market-2/amp/

Maryland Food Collective. (2024). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Maryland_Food_Collective&oldid=1250511163

Maryland State Grange. (n.d.). About Us. Retrieved June 6, 2025, from https://www.marylandstategrange.org/about-us

Maryland.gov. (n.d.). Register Your Business Online. Business Entity Search. Retrieved April 13, 2025, from https://egov.maryland.gov/BusinessExpress/EntitySearch

Morgan, D. (2024, August 21). Celebrating 50 years: The story of Frederick’s co-op grocery store, The Common Market | Arts & entertainment | fredericknewspost.com. Frederick News Post. https://www.fredericknewspost.com/news/arts_and_entertainment/celebrating-50-years-the-story-of-frederick-s-co-op-grocery-store-the-common-market/article_0b2665f9-c990-561d-b52c-cc8fb9651d6a.html

Nembhard, J. G. (2014). Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice (1st ed.). Penn State University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780271064260

O’Brien, C. (2023, March 10). Food sovereignty gains foothold in impoverished Baltimore community. AGDAILY. https://www.agdaily.com/features/black-yield-institute-food-sovereignty-gains-foothold-in-impoverished-baltimore-community/

Schneiberg, M., King, M., & Smith, T. (2008). Social Movements and Organizational Form: Cooperative Alternatives to Corporations in the American Insurance, Dairy, and Grain Industries. American Sociological Review, 73(4), 635–667. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25472548

Steinman, J. (2019). Grocery Story: The Promise of Food Co-ops in the Age of Grocery Giants (1st edition, p. 281). New Society Publishers.

Tuesday, C. P. |, August 09, & 2011. (n.d.). Passion for Food: Baltimore Food Co-Op Opens Its Doors. Bmore. Retrieved April 13, 2025, from http://www.bmoremedia.com/features/baltimorefoodcoop080911.aspx

Wholesome Harvest Food Co-op. (n.d.). About Us. https://wholesomeharvestcoop.com/about-us-1

Wholesome Harvest Food Co-op. (2022, June 30). Wholesome Harvest Food Co-op [Facebook]. https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=4729922050442589&set=a.433046335497359

Wilson, T. (2022, July). The Grand United Order of Odd Fellows Lodge. Baltimore Heritage. https://explore.baltimoreheritage.org/items/show/716