A Dose of Hope

The pinpoints of a dozen CCD spaces across a half-mile radius laid out a vision for the possible future of CCD in this historic West Baltimore community.

Around lunchtime on July 10th in Baltimore's Penn-North neighborhood, emergency personnel responded to a mass overdose event involving more than 25 people. The victims were rushed to the hospital, some in critical condition. Testing later revealed an unusual sedative mixed with fentanyl was to blame for what could have been a mass casualty event. The incident drew national attention; CBS News, People, AOL, and Yahoo all published articles detailing the event, alongside reporting from The Baltimore Sun and a statement from Mayor Brandon Scott.

Earlier that same morning, I had arrived at a storefront in Irvington, a neighborhood in West Baltimore, about ten minutes away from the site of the overdose event. I drove up for a meeting with the leadership of Cooperative Community Development Inc (CCD) that would draw no national attention. I parked next to a Dollar General and took note of the storefronts that I passed on the way to the office address I had been given. I was ostensibly there to talk about the feasibility of a cooperative grocery store, so scoping out the competition is second nature. The block had several small businesses including two corner marts, a small church, and a Chinese carryout.

I was invited by the leadership of CCD and a nearby co-op, Catonsville Co-op Market, to spend the day and tour their spaces. They had come to visit my co-op TPSS in Takoma Park, Maryland a few months beforehand. Our spaces are a mere 31 miles apart, but also a world away. The average household income in parts of West Baltimore is less than half that of all Maryland households.

I arrived at the small storefront with two large plateglass windows. In the window was a piece of wood the size of a tree trunk with the CCD logo carved into the face. A large split in the wood began at the outside and traveled into the middle of the logo getting smaller as it went. I found myself momentarily transfixed by the beauty of such an obvious imperfection.

I walked into the office and greeted two members of the Catonsville Co-op. The three of us chatted about the morning plan while we waited for our host. I wandered around the office whose walls were covered with maps of the neighborhood. The pinpoints of a dozen CCD spaces across a half-mile radius laid out a vision for the possible future of CCD in this historic West Baltimore community.

The door swung open with Kramer-entering-Jerry’s-apartment gusto. In strolled Johnny Martin Jr. standing tall and sleek. He wore a green reflective landscaping shirt, having just come from dropping off workers from CCD Clean & Green environmental stewardship team. His jeans tapered at his ankles, exaggerating his movements. Martin made eye contact through tinted glass as he greeted the assembled group and informed us that we would be joined by City of Baltimore staff from the BMORE Beautiful initiative.

The first two city staff members arrived and Martin, wasting no time, began to show us around the office space. Martin opened the door to an unfinished storage room at the back of the property. As one not unfamiliar with a messy “back of house,” I felt unfazed to walk in. The space was unfinished wood beams and exposed brick surrounding a single small white toilet. Not much to look at or think about. I was ready to leave when Martin began to explain his vision. This 4x8 foot space wasn’t just a toilet surrounded by dusty shelving. He saw a shower that would be open to those impacted by homelessness who had nowhere else to clean up. Martin saw the spaces of CCD not as they exist today, but their potential.

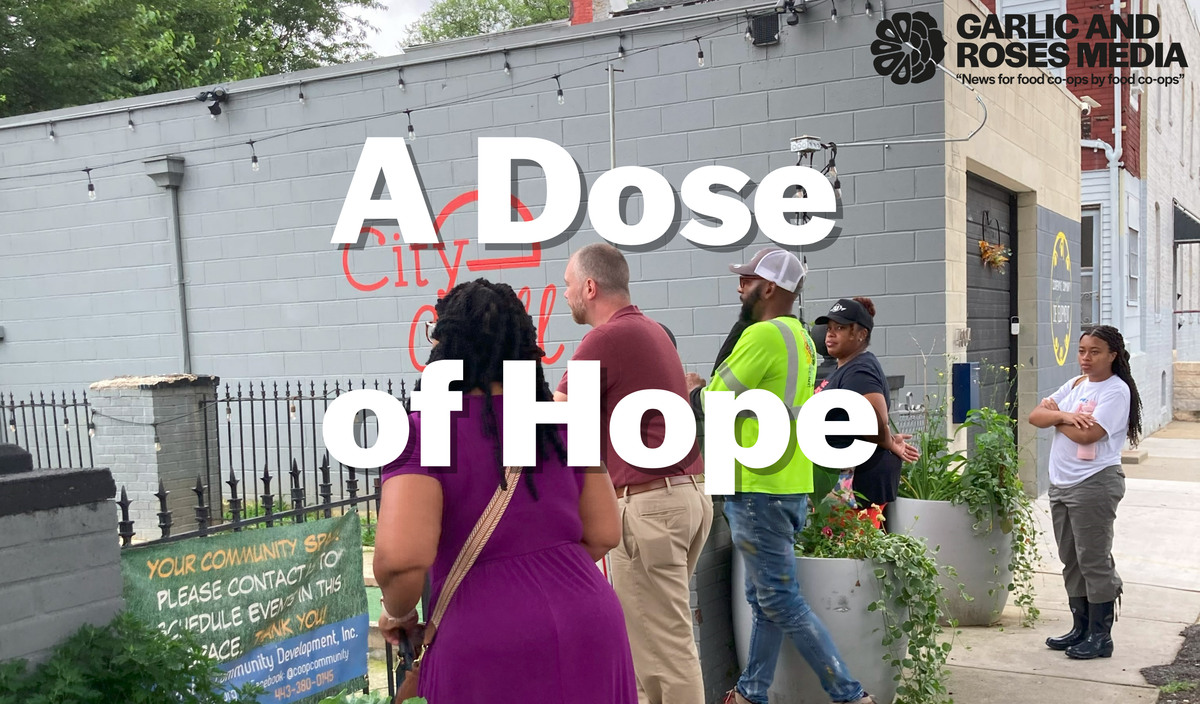

The group exited the office and met two more city staff members on the street. We eschewed introductions or icebreakers because Martin was already in the middle of a monologue about CCD’s youth program. He pointed to broken light posts and overgrown ferns from the cemetery across the street that blocked a view of the crosswalk signal. He explained how CCD taught civic engagement by encouraging young people to use 311 and report these mundane issues around their neighborhood that affect quality of life. He said that teaching them to advocate for what their community needs was important. He also pointed out that after his previous calls the overgrowth had yet to be trimmed, but he would simply keep calling until it was.

Still in the middle of his point on civics, the group followed Martin across Frederick Avenue to a small garage on the northern side of the street. CCD purchased the garage through a non-extractive loan from the Baltimore Roundtable for Economic Democracy. Martin flipped through his large ring of keys to the correct one, entered through a side door and forced open the large garage door for the group. Inside the garage I made eye contact with all manner of items tucked away for a future CCD project. A refrigerator, some mismatched chairs, heavy duty shelving and extension cords among other things all waiting patiently to be of use.

Martin took us back out the rollup door and to the side of the grey garage. A patch of land no bigger than a living room and surrounded by an iron gate was another piece of CCD’s empire of possibility. CCD had named the area “City Chill” but members of the youth program just called it “The Chill”. Martin explained the various ways the space had been used to that point, and the growing wish list to make it even better. A string of Edison bulbs criss-crossed the space above The Chill. They would have looked quite nice, but they were turned off because the outdoor power outlets were being used without permission.

Martin then led the group to the space that had first caught my eye. It was a three-story building of painted dark grey bricks, with the windows all boarded up. The future plans for this space were a little easier to suss out than the others, because they were bolted to the side of the building. Four large vinyl banners with architectural plans and renderings assigned future uses to the areas inside. CCD calls the space the Center for Social Impact. The upper floors would host office space for CCD, a life skills development center, a recording studio and an art gallery. The first floor was the hopeful future home of a co-op grocery store.

Martin again forced open a heavy door for the group, this one a groaning 8-foot sliding barn door on an old track that needed lubricant. The large open space contained more mismatched items–wooden tables, scooters and bicycles. The interior was the starting shot of any movie montage where the group magically fixes up a crumbling edifice. The Sister Act convent, the Ghostbusters firehouse, this space was ready for its montage. CCD had started some preliminary construction work, mostly framing out the walls of the future spaces. Martin pointed to dark spaces along the 4000 square foot first floor, calling each by its future use. The banquet hall is back there, the entrance to the store is up here.

We walked through two doors into a much brighter space in the front of the building facing Frederick Avenue. The white walls were broken up by several large windows, one of the few rooms in the building to have them installed. I began to count available shelf space along the walls in my head while Martin addressed the group. The thought was that the small market could provide the types of food that were unavailable in the immediate area. It would feature fresh fruits and vegetables and healthy alternatives to processed snacks. The storefront would be the literal and figurative entrance to the wider development work CCD was doing in the community.

Irvington, like much of West Baltimore, was listed on the city’s 2024 Healthy Foods Priority Areas report. Irvington has more historic cemeteries than it does full-service grocery stores. The city’s report lists priorities like “Attract and retain supermarkets” with no additional details.

After the Center for Social Impact, Martin took us to “cherry tree farm”. The space was about four blocks away and accessed via a normal gravel driveway. Walking up the path we could hear the loud squawk of chickens. A CCD volunteer was clearing brush. Martin showed the group to the wooden coop which housed chickens and two baby ducks. A chicken escaped the coup while Martin was getting one of the baby ducks and another CCD volunteer disappeared for several minutes before emerging triumphant with the sprung chicken in hand.

Martin envisions the farm producing local vegetables, fruits and eggs to be sold at the co-op market down the street. The buildout plan includes spaces for people to sit and enjoy live music and other agricultural programming. The BMORE Beautiful team was especially enamored at the possibilities of the space. They were also acutely aware of the permitting and paperwork that would have to accompany the physical transformation work. The city could hopefully lend a hand in that work, having identified another priority that said “Support urban agriculture, emphasizing historically disenfranchised populations and geographies” in that 2024 report.

Our last stop was next door, connected in fact, to the building where we started. The “teahouse” was perhaps the most decrepit of all the buildings we had seen. It shared a wall with the office space on Frederick Avenue. Martin described a first-floor coffee house called “4th Brew” featuring locally made baked goods. The second floor would house small retail entrepreneurs selling jewelry, books and more.

Martin and CCD have big ambitions for what is possible in this community. An interconnected multi-building hub of civil engagement, local food production, artistry and enterprise. Giving new purpose to underused and long blighted-spaces. Getting any one of those off the ground would be a feat. In front of them lies maddening bureaucracy to try to bring something better to an area that’s been systematically underinvested in for years. If anyone should be handed the magic red-tape scissors, it’s someone like Martin.

On July 2nd, a week before the Penn-North overdose event, the Baltimore Mayor’s office released a 20-page document titled “Overdose Response Strategic Plan”. The plan discusses strategies that could be put into place with funds from lawsuits with opioid manufacturers including the City’s lawsuit against Purdue Pharma. A section on Page-7 stuck out after my day with CCD. It said, “The City has an incredible opportunity to invest dollars back into the community, to reduce the impacts and prevent future harms.”

The report continued, “Social determinants of health are factors that affect health outcomes, including economic stability, social and community context, neighborhood and built environment, health care and quality, and education access and quality. Activities that address social determinants of health may include those that expand and increase the availability of comprehensive support services, such as healthy food, health care, education, housing, transportation, job placement/training, and childcare.”

Opioids have devastated large parts of Baltimore. It takes a special person to look at these neighborhoods and see them not as they are today, but what they can be in the future. A visionary in tinted glasses and skinny jeans who won’t stop moving and advocating until the work is done.

Comments ()